ScapyCon - MOTRA Testbed for OT-Applications

An introduction to the MOTRA research testbed, developed at LaS3 to enhance industrial security solutions.

The growth in networking between IT and OT is leading to increasing cyber threats to critical industrial systems. As more and more cross-system protocols such as OPC UA and cross industry services are being integrated into modern embedded devices, new security-related challenges are emerging. The presentation for this years ScapyCon discusses the problem of complex OT architectures based on the example of OPC UA and then presents a container-based testbed for reproducible attacks. We hope anyone who saw the presentation could gain insights into industrial applications, the design of vulnerability-specific tests and the handling of virtual systems in the testbed.

Checkout our main contributions: Frozenbitz and DocDriven - Motra Setups and Motra Images

Why do we need a testbed for security applications in the first place?

Getting data for anomaly or intrusion detection is currently a problem for our team at OTHR, since the available data is either very old or the quality of third party datasets is of questionable quality. In a more general sense, depending on the use case, there is very little data available for our current target systems.

For our ideal setup we have different requirements when working inside a testbed:

- We require direct access to the network, to get feedback for our NIDS based system

- We require direct access (kernel level) to industrial devices, since live data from low level hardware is needed for our HIDS

- We need a flexible setup to test to integrate our interactive solutions

Getting industrial hardware is expensive (and often requires licensing), usually requires additional software and is most of the time not plug and play. Also most industrial setups offer no tool support for virtual or hybrid setups, which would be a big bonus in our case, because it would allow for more flexible and fast paced development.

So we thought, can we build a custom testbed for our own industrial use case?

Our protocol of choice will be OPC UA for our prime target inside the testbed. There seems to be a lack of applications targeting this protocol, as far as we could see from recent literature in OT security contexts. UA Automation has a good introduction to OPC UA and all the layers involved for the different protocol aspects here.

OPC UA is an open standard that is being supervised by OPC Foundation. Tools, reference implementations and public standard documents are available online, free of charge. Due to the openness from the different standards and the available reference stacks there are also a lot of customized implementations for OPC UA for other programming languages and frameworks. This allows usage of the core stack in many different applications and industries. In addition there has been work on OPC UA supply chains and vulnerabilities by third parties over the last few years (Claroty/Team82), including public exploits and vulnerability assessments.

OPC UA covers different types of services (in standard wording: the service model) and customizable object and information models. These can be used to interface applications and build highly complex information structures for sharing and transforming application data from all sorts of data sources. In addition recent changes added complex management functions for the different discovery server options, allowing OPC UA to integrate certificate management into more recent deployments. This allows the already existing security architecture to cover even more applications and integrations.

How did we build it? Starting with the server components.

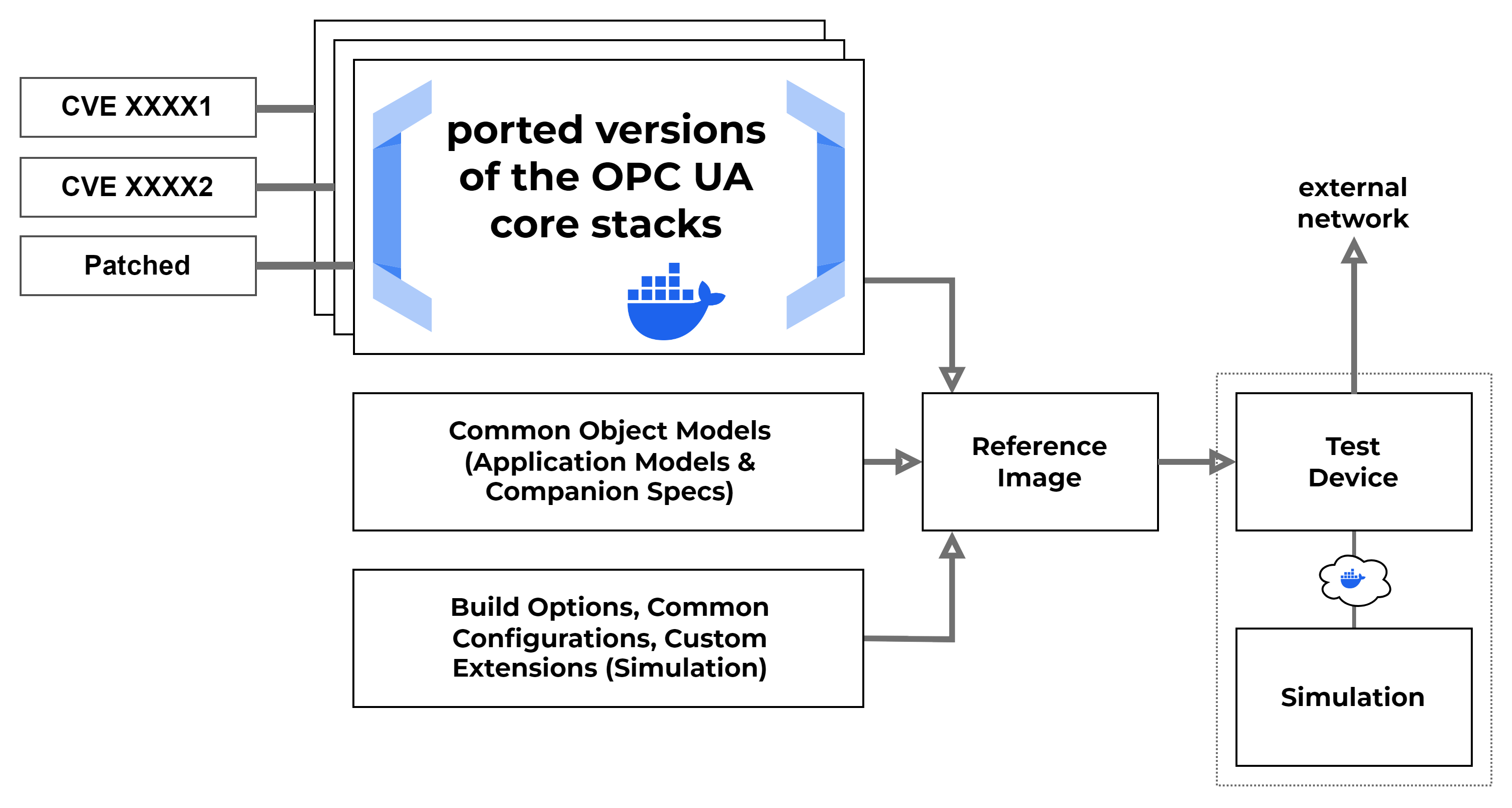

Building of the different components started initially with the different OPC UA servers using a containerized setup. The main problem we were facing was the availability of good quality data for IDS research purposes. Therefore we wanted to build a setup that allows us to run different attacks against different target setups with different software versions, so we could investigate how changing the setup under certain conditions would change the measurements and the impact on different IDS solutions.

OPC offered a very nice solution in this case, since the publicly available model compiler1 can be used to create a custom information model, that is portable across different software stacks and over different versions of the stack implementations. Therefore we could build on a common framework and get near identical behavior for the different instances of our OPC UA servers. As an added bonus, when building the entirety of our services as containers, we could add a networked simulation to another docker container and hide the simulation inside the docker stack, only exposing the system we wanted to test. This made integration of other services and simulation solutions quick and easy.

By adapting more configurations, we also added more details to the container build process. This allowed us to quickly build more flexible setups, because swapping containers also meant changing the server configuration and changing specific vulnerabilities inside the setup. When experimenting with these features we found, that we could build setups tailored to specific vulnerabilities at specific locations inside the current testbed location. This made it possible to create an customizable setup, that would allow us to run tests and attacks with very specific attack paths in mind.

In our first attempt, we built the different versions using our build configurations, custom object models and our OPC UA server ports, as can be seen in the image above. These were used as our reference images in the testbed. When building the reference images, we used a sort of fixed setup for configuring each container. One example can be seen here. Each component uses build and run scripts to create a new container image from scratch. Configuration is done over the currently active environment and defaults are applied using the different bash scripts. This allows to integrate the builds into different frameworks like GitHub Actions or similar tools. Configuration of more complex setups is done using docker build contexts or so called named contexts.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

CONTAINER_CONTEXT=${CONTAINER_CONTEXT:-$(realpath .)}

docker build \

--build-context container_context=$CONTAINER_CONTEXT \

--build-context nodeset_context=$NODESET_CONTEXT \

--build-context companion_context=$COMPANIONSPEC_CONTEXT \

--build-arg NODESET_MODEL=$NODESET_MODEL \

. \

-t node-server

For example, we can use realpath to generate a valid path to an existing configuration folder. The build context flag can then create a named context, in this case container_context, to pass additional information into the build process for docker. This feature is important, because all build steps for docker and compose support this type of configuration and because this configuration is not limited to a local file. A named context can also be a repository or a remote resource known to docker. This allows us to pull in remote configuration content into our build process on the fly.

Referencing of the contexts is done inside the Dockerfile using the names from the command line. Supported build instructions can make use of named contexts to pull in metadata or configuration files from external sources. Also this sort of build is not limited to a single folder containing the Dockerfile, but can pull in data from custom sources.

1

2

3

4

5

...

COPY --from=container_context src/* /usr/src/app/

RUN npm install

ENTRYPOINT [ "/usr/bin/env" ]

CMD [ "./entrypoint.sh" ]

Building the Component Library

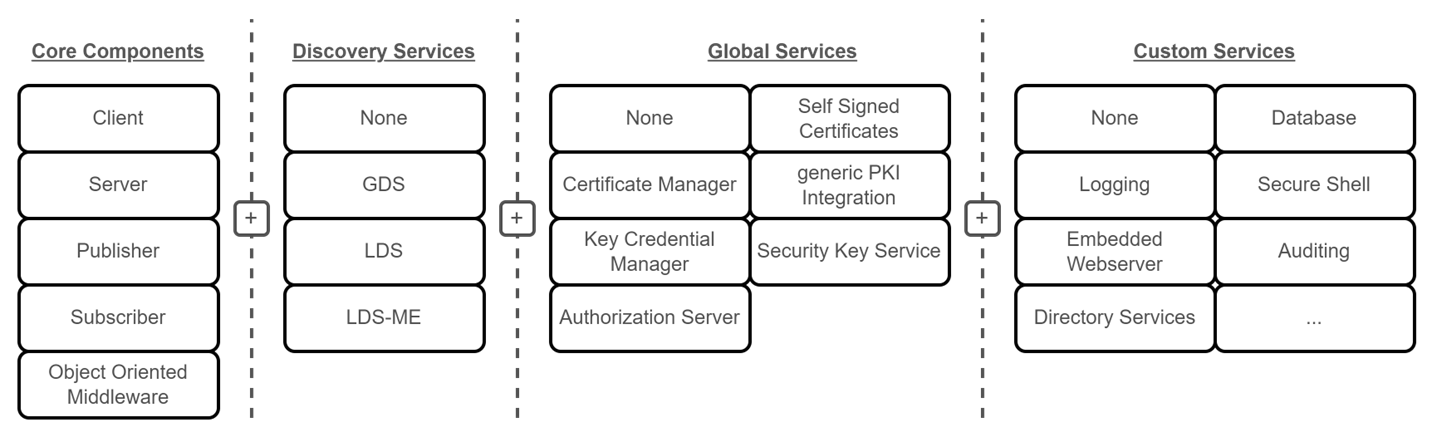

Using the knowledge we got from experimenting on the server we started to prepare a more general approach to working with our testbed container instances. We planned for deploying the different units as stand alone Docker containers that could be customized and combined to be used in different setups for pentesting or education purposes. A set of our components can be configured to mock existing (vulnerable) industrial devices or services, by setting up the core components with added services and providing shared resources for all containers for a specific application. Each container serves as an isolated process by default, but the combination of different building blocks creates a single (possibly vulnerable) application, depending on the services, components and resource configurations used.

The general component library from our previous work on IEEE2

The general component library from our previous work on IEEE2

How can we setup devices or applications?

To use the testbed, we provide a set of samples in our setups repository. For the most basic use case, we can override or customize an existing image using docker or docker compose on the host we wish to configure. Next we can choose a device model, if we want to run a specific type of OPC UA node. For the current testbed iteration, we have some sample nodes to simulate a water treatment process. These models can be used as is or modified for another use case. To run the final image locally, we need to store the final configuration either on an available git server or locally on our file system. To run a stack of components or a single image, we use docker run or a more complex compose file to mock an industrial device.

Configuration of our devices can be done using named contexts in docker and docker compose. These can be passed into different steps during build time and can pull in data and configurations from a number of different sources. This also lets us override the default configurations, security settings and sample models available on the different server images in our GitHub. As an added bonus, docker compose can pull in data from remote sources using before mentioned named contexts. This allows us to run a fully configured industrial device node on custom hardware using only a single configuration file, if the network is setup correctly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

services:

plc-server:

container_name: "plc-server"

build:

context: ${IMAGE_REPO_URL}#main:opcua/server/nodejs-node-opcua/latest

args:

NODESET_MODEL: "PLC.NodeSet2.xml"

additional_contexts:

container_context: ${IMAGE_REPO_URL}#main:opcua/server/nodejs-node-opcua/latest

nodeset_context: ../meta/demo-nodeset2

companion_context: [...]

plc-historian:

container_name: "plc-historian"

- [...]

plc-logic:

container_name: "plc-logic"

- [...]

build:

context: ${IMAGE_REPO_URL}#main:opcua/plc-logic/python-opcua-asyncio/latest

networks:

- [...]

Note the named sections inside the build and additional_contexts blocks: container_context, nodeset_context & companion_context. These can be used to override configurations, build settings and even some runtime options from local or remote sources during the build steps. The only downside of these options is, each folder or location needs to exist. Every context needs to provide some default location for docker to finish a build job.

References

P. Heller, S. Kraust and J. Mottok, “Building Modular OPC UA Testbed Components for Industrial Security Pentesting,” 2025 International Conference on Applied Electronics (AE), Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2025, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1109/AE66163.2025.11197826. ↩︎